Packera Pursuit

Packera Pursuit

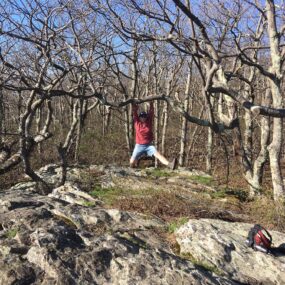

I am being followed. Or, rather, I am following. I keep glancing over my shoulder to see if it is still there. Not because I feel threatened, but because it is cheering me along, whether on foot or bicycle. The subject is Packera aurea, known commonly as golden ragwort or golden groundsel. Packera is unflinchingly cheerful. If you are following Packera, you are likely in a wooded setting on a rocky ridge or a floodplain or maybe a rain garden, and it may be early or late Spring. How fortunate for you!