Another Dam Done Gone

The crowd of close to 3,500 gathered on the riverbank of the Rappahannock River in Fredericksburg, VA on February 23, 2004. They had come to see the explosion. The atmosphere was celebratory, even jubilant, with dignitaries and media buzzing around. The crowd had come to see the Embrey Dam be blown up by an Army Engineering team from Fort Eustis, ultimately opening up 700 miles of river and tributary waters to migratory fish and creating a unique river paddling experience. John Warner, a U.S. Senator from Virginia at the time, donning his floppy brimmed fishing hat, pushed the symbolic demolition plunger, and the crowd held its collective breath.

When a dam on a river has been a part of a community’s economic, cultural, and environmental fabric for a century or more, it is hard to imagine that river and that community without the dam. It takes imagination, vision, and a compelling story to muster the community support, funding, permits, and political will to remove the dam. And it takes something else. . .persistence.

In Fredericksburg, the Embrey Dam was one of a pair of dams on the Rappahannock, the first of which was a wood-and-stone crib dam constructed in 1854 as part of the canal system and to turn many millstones along the canal’s path.

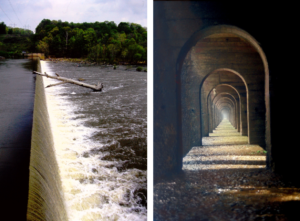

The Embrey Dam was built a short distance downstream in 1910 to generate electricity for the growing City and, later on, to divert water for the City’s drinking water treatment plant. The Embrey Dam was “built for the ages,” constructed with the slab and buttress technique, 22 feet high and 728 feet across. It was not something considered moveable to any degree.

Left: The Embrey Dam was built for the ages using the slab and buttress technique. The dam was 22 feet high and spanned the River for 728 feet. Right: A view of several of the fifty-six arches that served as supporting buttresses in the structure’s inspection gallery. Photos: Tom Van Arsdall.

Between the 1970s and the 1990s, all of the original purposes of the Embrey Dam were replaced by other resources. The water supply intake was abandoned due to a regional water deal and new reservoir on Motts Run. Hydropower was replaced by other sources of electricity. Yet, the dam stood, a silent sentinel to its historic utility. The community could hardly imagine “the Rapp” without its dam, a river landmark for over ninety years. However, if you ever had to portage your canoe or kayak around Embrey, after a dozen or more trips schlepping your boat over steep, muddy terrain, your imagination may have taken you there.

Indeed, the Friends of the Rappahannock (FOR) had been advocating for dam removal since the mid-1980s. It started as a twinkle in the eye for several FOR Board members. The compelling reasons for dam removal were river recreational access, eliminating a liability for the City as the dam owner, and restoring passage upstream for fish, such as American shad, hickory shad, and herring.

These species are categorized as “anadromous,” meaning that they live their lives in salt water, but return to the freshwater rivers of their birth, including the Rappahannock, to spawn. Dams like Embrey blocked the pathway and availability of upstream waters for this essential aquatic life cycle.

For dam removal projects, it’s a long journey from the notion that it would be a good idea for multiple reasons to actual removal of the structure. As with other dams, Embrey had accumulated many tons of sediment over the years. “Many tons” may be a gross understatement for a sediment plume 700 feet wide and over 20 feet deep. Furthermore, there was concern about this sediment harboring contaminants, such as Mercury, due to historic gold mining operations upstream. With the Chesapeake Bay clean-up still in its early phases, the last thing FOR wanted to do was release tons of sediment downstream into the Rappahannock and down to the Bay.

For these reasons, an early step for FOR was to advocate for sediment testing, which was ultimately funded by the Virginia General Assembly. It was fortuitous that the study revealed that the sediment was more-or-less clean of contaminants, but the unresolved issue was still if and how to remove so much sediment if the dam were removed.

And then there was the issue of funding such a large project – perhaps on the order of $8 to $10 million. Enter U.S. Senator John Warner. During a tough re-election campaign in 1996 (pitted against the aptly-named and now U.S. Senator from Virginia, Mark Warner), John Warner made a campaign stop in Fredericksburg, and had some extra time. Due to some D.C. connections with FOR board member Tom Van Arsdall, Warner met with several FOR representatives. The assembled crew took a stroll up the canal walk to the base of the dam. Along the way, Warner heard about the hopes and dreams for removing the structure, and this seems to have captured the Senator’s imagination.

Warner expressed support for dam removal, but only if the community was 100% percent behind the effort. He could not afford to expend political capital on a well-meaning project as long as there was push-back within the community. To FOR’s credit, the organization and its partners, including the City of Fredericksburg, took this to heart, and spent several years educating the local community about the amazing resources along the River and benefits of removing the dam.

One notable event occurred on Earth Day, 2000, with not only Senator Warner, but also fellow Virginia Senator Chuck Robb and plenty of media coverage. The event featured volunteers in boats netting stranded fish below the dam and ferrying them to a bucket brigade on the riverbank. The bucket crew passed the fish from hand-to-hand, up and over the dam in a visceral demonstration of one of the key benefits of dam removal.

Indeed, the dam was preventing fish migration into 700 miles of upstream river and tributary waters, where they had been excluded for over a century. It is reported that during the press briefing for this event, FOR Executive Director at the time, John Tippett, mimicked giving mouth-to-mouth resuscitation to a fish to restore it to health for the upstream journey.

Left: Volunteers net stranded fish below the dam during the Earth Day 2000 event. Right: More volunteers formed a bucket brigade on the riverbank to ferry the stranded fish up and over the dam, demonstrating in a visceral way one of the key benefits of dam removal.

The next chapter in the story of Embrey’s removal is all about fish and politics. The two are indeed linked, as any observer of Virginia politics can attest (the annual political event known as the Shad Planking is a case in point). In the case of the Embrey dam removal, this started as a fishing trip for Senator Warner with several of the Rappahannock river rats, and the Senator’s declaration, “I’m going to take that dam on as a personal project.” The Senator had the political might to do such a thing, as a member of the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works. The Senator was the key instrument to secure funding for removal through the Water Resources Development Act, including waiving the customary non-Federal cost-share, which was not an insubstantial sum.

The irony here cannot be lost as a sign of the times, as the Water Resources Development Act and its various incarnations was used historically to construct impoundments for the purposes of navigation, flood control, and other directives of the Army Corps of Engineers. Here we see an instance of funding through the Act being used to undo previous development of river infrastructure for the purpose of restoring an aquatic ecosystem. As stated previously, fish and politics go well together.

Before actual removal could occur, there remained the issue of that massive pile of sediment trapped behind the dam. The cheapest approach was to create a small breach prior to removal of the full structure and let the sediment trickle slowly out downstream. This was an alarming prospect for FOR, as the group was also supporting restoration efforts in those earlier days of the Chesapeake Bay Agreement. While long advocating for dam removal, the group did not want to condone the release of sediment as collateral damage from the project.

Ultimately, the Army Corps decided to remove the sediment in the main river channel area, necessitating a massive dewatering and dredging operation. A load of sediment equivalent to 50,000 dump trucks was eventually removed from Embrey’s backwater channel. Fortuitously, a local composting company was able to use some of the sediment, mixing it with compost to create “Rappahannock Gold.” While this removed a sediment source from the river channel, sediment along the adjacent floodplain areas would still wash slowly downstream, one of the realities of removing a structure that had been blocking upriver sediment for over ninety years.

Demolition day had finally arrived. The nearby Interstate 95 was shut down as a safety precaution. A large digital clock counted down, and Senator Warner pushed the ceremonial plunger. A small puff of smoke erupted from the dam, and a bit of water spilled through the breach. The crowd was expecting something much more spectacular. Many packed up their folding chairs and headed home. They should have stuck around for the real show.

As it turned out, only one out of the ten explosive clusters had gone off, with the small explosion cutting the line to the remaining nine. Those who remained were rewarded with the full show about an hour later after the Fort Eustis team fixed the problem. A compression wave rolled through the crowd as the remaining nine charges erupted, and the Rappahannock spilled with great gusto through the expanded breach, creating the upstream to downstream water link for the first time since the 1850s.

U.S. Senator John W. Warner (left) and John Tippett, Executive Director of the Friends of the Rappahannock at the time (right) address the crowd at the ceremony on February 23, 2004 prior to the actual detonation of the explosives. Photos: Tom Van Arsdall.

Left: The explosive clusters planted by the 544th Engineering Dive Detachment from Fort Eustis go off with fanfare after the first smaller explosion an hour earlier. Right: The Rappahannock River spills through the breach, re-uniting upstream and downstream for the first time since the 1850s, and creating one of the longest free-flowing rivers on the East Coast (right).

The dam removal restored the Rappahannock as one of the East Coast’s longest free-flowing rivers.

It took about a year for the demolition to be completed, as the dam was taken down piece-by-piece.

After the removal, pieces of wood from the upstream crib dam took on a new and unexpected life. Norm Abrams from the PBS show, New Yankee Workshop, travelled to Fredericksburg to film a show in which he used pieces of the old crib dam to create George Washington style furniture, a fitting rebirth to link the history of the region to current events.

Over the years, the expected upstream movement of shad and herring has been confirmed by the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources.

The Embrey Dam removal opened up more than just the Rappahannock River. In some ways, it helped accelerate the idea that removing obsolete dams could have wide-ranging benefits, and the effort could be successful if the right stars aligned. The group American Rivers reports that sixty-nine dams were removed in 2020 alone, and 1,797 dams have been removed across the country since the early 20th century.

Many of those who paddle a canoe or kayak through the shoals and rapids of that stretch of the Rappahannock today probably have little inkling that those rapids had been long-buried under the Embrey Dam’s backwater. They may not realize that the once-sturdy dams provided navigation, hydropower, and drinking water to a growing region of Virginia.

And perhaps that is as it should be. With a keen eye on the next rapid, an excited flutter of the heart, and surrounded by the miracle of moving water, it’s what’s being on a free-flowing river is all about.

— David J. Hirschman, dave@hirschmanwater.com

I want to extend my full gratitude for John Tippett and Tom Van Arsdall for relating their personal reflections on the Embrey Dam removal.

Take a look at the other articles in this series about the building, maintaining, and removal of dams:

The Damming of America’s Rivers

References

American Rivers. 69 Dams Removed in 2020. February 18, 2021.

Dennen, Rusty. River has run free for 10 years. The Free Lance-Star. February 15, 2014.

Pezzullo, Elizabeth. Celebrating a dam’s demise. The Free Lance-Star. February 24, 2004.

Tippett, John. Personal communication. October 6, 2021.

Van Arsdall, Tom. Personal communication. October 15, 2021.