2022 marks the 50th anniversary of the 1972 passage of the Clean Water Act. Three years prior to that milestone, on June 22, 1969, the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland caught fire. As the narrative goes, this conflagration was one of the chief galvanizing events to build support for cleaner water in the country. A river on fire was a striking emblem of the condition of the nation’s waterways. Was this the only time the Cuyahoga caught on fire? No. Was the Cuyahoga the only river in the U.S. to have such mishaps? Far from it. The reason the 1969 fire has become imbued with historical precedent has much to do with two brothers: Carl and Louis Stokes.

The Stokes brothers grew up in public housing in Cleveland. Their father worked at a laundromat and died when the boys were young. Their mother cleaned houses for people in Cleveland’s wealthy suburbs, and the boys were raised largely by their maternal grandmother. Carl went on to become the first Black mayor of a major U.S. city and Louis served for 30 years in the U.S. House of Representative and was a member of the powerful House Appropriations Committee.

Together, the brothers had a profound impact on policies and investments linked to cleaning up the Nation’s waters. However, their motivations went far beyond clean water.

The Cuyahoga caught fire numerous times between 1868 and 1952, and many of these were much more destructive in terms of property damage and loss of life than the now-notorious 1969 fire, which only lasted 30 minutes (Boissoneault, 2019). However, the previous fires were seen as the price to be paid for a booming economy and the employment it brought. The banks of the Cuyahoga were home to ship building, paint, steel, and oil industries, among others. During that time, it was common knowledge that if you fell, surely by accident, into the river, it meant a trip to the hospital.

The Industrial Revolution turned Cuyahoga River corridor into an intensely industrial landscape represented by ship building, paint, steel, oil refining, and other industries. The economy was booming, until the late 1960s. Images: National Archives. Left: Cuyahoga river winds through Cleveland (1940). Right: One of many industrial discharges into the Cuyahoga (1973).

The June 22, 1969 Cuyahoga fire lasted only 30 minutes, so brief that no one managed to get a photo of the now notorious fire. This photo of firemen putting out the fire is likely from a previous Cuyahoga fire in 1952 (Boissoneault, 2019). Image: Cleveland Public Library

There were efforts to protect the City’s drinking water source, but generally, the economic benefits were paramount. This storyline changed in the 1960s when manufacturing jobs started migrating overseas. Cleveland alone lost 60,000 such jobs during the period (Boissoneault, 2019). Cities were hurting in terms of employment, housing, and racial injustice, and the Country was consumed by the Civil Right Movement and the Vietnam War. A horrible river was emblematic of wider social dysfunctions.

It was in this context that Carl was elected Mayor in 1967 after serving in the Ohio House of Representatives. It was Carl Stokes’ political acumen that turned the 1969 Cuyahoga River fire into a clarion call. The day after the fire, Carl led a press tour, known as the “Pollution Tour,” calling attention to the befouled river and it’s linkage with the City’s deteriorated housing stock, poverty, and lack of proper wastewater treatment. The main thing was the need for investments all around. In fact, Carl would not have considered himself an environmentalist, but a champion of what we now call environmental justice (Musetti, 2021).

On the first Earth Day in 1970, Carl in quoted as saying, “I am fearful that the priorities on air and water pollution may be at the expense of what the priorities of the country ought to be: proper housing, adequate food and clothing” (National Park Service, 2022).

Meanwhile, Louis Stokes was elected to Congress in 1968, the first Black person to represent the State of Ohio. Prior to his election, he was a prominent attorney, working on cases such as fighting the Ohio legislature’s 1965 redistricting that diluted the Black vote. That case ultimately went to the U.S. Supreme Court and it was Louis’ legal brief that formed the basis of the decision against the redistricting (U.S. House of Representatives).

In Congress, Louis championed many of the same causes as his brother, such as investments in job training, housing and urban development, education, veterans’ issues, wastewater treatment, and environmental regulation, including the Clean Water Act. Among other accomplishments, he was formative in the establishment of the Congressional Black Caucus.

Though serving in the U.S. Congress, Louis considered his brother Carl as the real politician and mover and shaper. Indeed, after serving as Mayor, Carl went on to be a television news anchor in New York City, judge, and U.S. Ambassador to the Seychelles. The two brothers talked every day about policies, strategy, and issues. Louis retired from Congress in 1998, two years after Carl passed away from cancer.

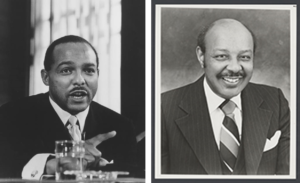

Carl B. Stokes (left) was the first Black mayor of a major U.S. City and served in that position from 1968 to 1972. Louis Stokes (right) served 15 terms (30 years) for Ohio’s 11th congressional district, championing many of the same causes as Carl. He served on many committees in addition to the House Appropriations Committee including the Select Committee on Assassinations that investigated the assassinations of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr.

The Cuyahoga River today features a glimmering skyline, a swath of green along the river, and kayaks and paddleboards navigating the waterway. There are still impairments under the Clean Water Act, but the transformation is astounding, even if incomplete. I think the Stokes brothers would marvel at the scene, but also wonder if all of Cleveland’s neighborhoods have equal access to the river’s benefits.

Cleveland, Ohio, USA downtown skyline on the Cuyahoga River at dusk. The modern Image: iStock photo ID:1055216368, Sean Pavone

Some have maintained that the Stokes brothers were ahead of their time in terms of championing the intersection of a clean environment with urban issues of public health and racial justice. That is certainly true, but it also the world they grew up and lived in. A polluted river afflicts the environment, the economy, public health, or any other measure of community vitality. As the Clean Water Act enters it’s next 50 years, the Stokes brothers’ legacy has proven to be a compelling and enduring one.

David J. Hirschman, dave@hirschmanwater.com

For another riveting Clean Water Act backstory, see my previous post:

NIXON, MY BIRTHDAY, AND THE CLEAN WATER ACT THAT ALMOST NEVER WAS

References

Boissoneault, Lorraine. 2019. The Cuyahoga River Caught Fire at Least a Dozen Times, but No One Cared Until 1969. Smithsonian Magazine, June 19, 2019. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/cuyahoga-river-caught-fire-least-dozen-times-no-one-cared-until-1969-180972444/

Musetti, Rachel. 2021. Remembering Mayor Carl B. Stokes for Bringing National Attention to Water Quality and Environmental Justice. Emory University, Sustainability Initiatives. February 8, 2021. https://sustainability.emory.edu/remembering-mayor-carl-b-stokes-for-bringing-national-attention-to-water-quality-and-environmental-justice/

National Park Service, Cuyahoga Valley National Park. 2022. Carl B. Stokes and the 1969 River Fire. https://www.nps.gov/articles/carl-stokes-and-the-river-fire.htm

Stokes, Carl B. Case Western Reserve University, Encyclopedia of Cleveland History.

Stokes, Louis, 1925 – 2015. U.S. House of Representatives, History, Art, and Archives. https://history.house.gov/People/Detail/22311