We have always known that long-term maintenance was part of the picture for stormwater BMPs. However, for many years, that notion was an annoying rattle in the background as we’ve gone about the often more gratifying work to design and install BMPs. Now, maintenance is front-and-center with any project. Most practitioners would agree that lack of adequate maintenance is unacceptable, as the result is not good for the site, for water quality, or for the property owners and public. Poor long-term maintenance also represents a huge betrayal of the initial investments of money, time, creativity, and energy we put into planning, designing, and installing the practices.

The movement to increase the complexity and diversity of species in our stormwater landscapes –bioretention, rain gardens, buffers, filter strips, and other vegetated practices – comes with additional maintenance implications. We want these practices to treat water quality, as is their fundamental intent, but also contribute to the ecosystem functions of the surrounding site, neighborhood, and region.

These types of practices are more complex from a maintenance standpoint. Maintenance crews must be able to identify the “good” native plants (i.e., don’t yank these ones out!) versus the invasives, have the right tools and equipment, and do a lot more hand work (and spend the attendant extra time) compared to the old mow and blow routine.

This dynamic tug and pull between BMP design and required maintenance has served as a foundational principle for programs like the Chesapeake Bay Landscape Professional (CBLP) certification program and its offshoots, such as field training for maintenance crews. CBLP and other programs managed by non-profits, local governments, and private interests are essential for the critical course correction on maintenance in our industry.

Over the years, I have witnessed more than a few BMPs succumb to the gravitational pull of “maintenance by weed whacker.” You probably have as well. Many of these BMPs started their life with robust planting plans and great aspirations on the part of the designers and site managers. Sometimes, the weed whacker transition occurs after eight or ten years of attempts to maintain the practices with cycles of excessive shagginess followed by the inevitable scalping. There may have been a maintenance plan, but likely a cut-and-paste job from the generic maintenance table in a state stormwater manual, copied onto a remote plan sheet in a file drawer or old hard drive. This is not what you would call a living document or one that is specific to the site and the practice in question.

Many stormwater BMPs start with diverse planting palettes (left side) only to succumb after several years of shaginess to “maintenance by weed-whacker” (right side).

I might add (with much-needed optimism here) that many MS4s in our region recognize these issues, take them seriously, and have allocated resources of budget and staff to address them. This also applies to several watershed groups that recognize that their great work to stimulate BMP implementation among public and private partners must be followed up with some type of cogent maintenance.

All of this propels the question of how to keep improving BMP maintenance. As one who likes put things in writing, I am reluctantly cognizant of the fact that hard-copy O&M plans get lost, have lots of coffee (and mud) spilled on them, and end up in the document equivalent of the junkyard. Maintenance crew positions are subject to turn-over, and any plan needs to be available in various languages and in electronic form on a phone or tablet that is taken out in the field. Someone (besides me) needs to develop an app! Or I’m sure someone already had done so.

In that spirit, here are some thoughts about improving our maintenance planning and communication.

But I want to begin this discussion at the design phase where it belongs. The various CBLP curricula emphasize the point to consider maintenance as part of the original design. The corollary to this is don’t design a practice that can’t be maintained by the responsible parties. However, this process of the designer working with the those responsible for maintenance is not formalized in any real sense. This process could take the form of a questionnaire that the designer works through with the responsible maintenance party, provided that that entity is known at the time of plan development. Here is a list, although not exhaustive, of questions that could be in the questionnaire.

Design Phase Questionnaire:

- Do you have a maintenance crew (or contractor) that maintains landscape features on a regular basis? Are stormwater BMPs part of this work?

- How many stormwater BMPs is the crew responsible for maintaining?

- What’s the frequency of maintenance visits: quarterly, semi-annual, annual, every 3 years, as needed, other?

- How much time does the crew typically have for each site: 30 minutes, 1 hour, up to 3 hours, other?

- What tools and equipment does the crew have available for maintenance: hand tools for pruning, cutting, digging, weeding; small mowers (capable of cutting high – approximately 6-8 inches); weed whackers, etc.?

- Are there concerns or restrictions about use of chemical herbicides (e.g., glyphosate)? What degree of chemical use is appropriate for the site?

- Has your crew had any training and/or experience identifying and working with native plants?

- Has your crew had any training and/or experience identifying and controlling invasive species?

The answers to these and similar questions would provide the design professional a realistic sense of how much maintenance will be performed, by whom, and its degree of sophistication. This information can be translated into design features, including the planting plan.

The next part of the improved O&M plan (or app) would be the more traditional maintenance tasks. While we have been including this type of information on plans for a long time, the elements outlined below would help make the plans more detailed and site-specific. Note that these elements borrow heavily from CBLP’s Sustainable Landscape Maintenance Manual (Corson, 2017), which provides guidance and many templates for maintenance planning for not only stormwater BMPs, but the broader context of sustainable landscaping.

1. Show graphically the components of the specific BMP:

Don’t assume that maintenance crew members will understand what is meant by terms such as inlet, outlet, overflow, inlet protection, energy dissipator, filter bed, gravel diaphragm, spillway. . .you get the point. The plan/app should show graphically each component and explain its purpose. Maintenance crews like to know not just WHAT to do but also WHY they are doing it to improve the function of the BMP and protect the environment. Tell them how the BMP is intended to function.

Excerpts from a BMP O&M plan that shows the various BMP components (left) followed by photos and description of each component (right). Source: Hirschman Water & Environment, LLC for Rappahannock Tribal Center.

2. Maintenance Tasks:

The main part of the plan is the task list – weeding, pruning, thinning, replanting, repairing erosion on side slopes or in the filter bed, ensuring inlets are still functional, and the list goes on.

Excerpt from a maintenance plan template developed by CBLP for the Maintenance Crews class. This table was adapted from CBLP’s Sustainable Landscape Maintenance Manual for the Chesapeake Bay Watershed (Cheryl Corson, 2017).

3. Task Frequency, Seasonality, or in response to Visual Site Inspection Triggers:

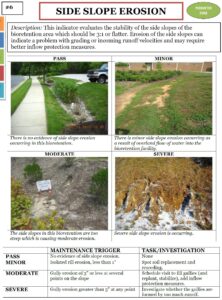

Maintenance crews must use their time efficiently, so this is an important consideration. The site inspection visual triggers are a great option as long as inspections are actually taking place! The triggers would include items such as percent cover by invasive or unwanted plants, accumulation of sediment in forebays and on the filter bed, debris accumulation at inlet points, and other visual cues. There are several very helpful resources that tie maintenance response to visual triggers on a scale of severity (the issue is minor, moderate, or severe). One such tool is the Chesapeake Stormwater Network’s Bioretention Illustrated. It is also helpful to approximate the time demands for specific tasks, as this translates to the maintenance budget.

Example of visual indicators to trigger maintenance responses. Source: Chesapeake Stormwater Network Technical Bulletin #10: Bioretention Illustrated.

4. BMP Life Cycle:

Maintenance will change through time, so the plan/app should articulate maintenance tasks during the BMP’s youth (initial establishment period — first two or three growing seasons), middle age, and elderly period (but hopefully not death). This is where adaptive management can at least be suggested. For example, if the BMP includes trees, as some point the BMP will transition to a shady environment, so vegetation must be managed accordingly to maintain robust vegetative cover on the ground level of the practice.

5. Routine vs. Non-Routine Maintenance:

Most of what is articulated above involves routine maintenance. In other words, maintenance that can reasonably be anticipated ahead of time. However, the unexpected will inevitably occur during the life of the BMP. A lot of this is tied to extreme weather on both the wet and dry side. Specific non-routine maintenance needs cannot be predicted, but the O&M plan/app can at least note those that are typical with various BMPs. The importance of this is that the O&M plan is tied (in the ideal world) to a maintenance budget, and non-routine responses are the most challenging to include in these budgets.

6. Tools, Equipment & Training/Certification:

The plan/app is not complete without this category. For instance, if the plan calls for mowing or bush-hogging the BMP to eight inches once per year in the late winter, then the crew must have the equipment to cut at that height. Other considerations are tools/equipment that will minimize soil compaction, allow for the efficient use of time, and respect the site owner’s desires about the use of herbicides, and of course site aesthetics. Finally, the training and certification are essential. Written guidance or an app must be accompanied by training that is appropriate to the maintenance crew audience (CBLP Crews is one example).

7. Level of Service:

While all BMPs should maintain their pollutant removal (and ecosystem) functions, not all BMPs need to be maintained to the same level of “orderliness.” A BMP next to the entrance of the public library, elementary school, or popular park may require a higher level of maintenance than one that is behind an industrial building or in a public works yard. The degree of public exposure may dictate different levels of service. The Seattle Public Utilities’ Green Stormwater Operations & Maintenance Manual does a good job of distinguishing different levels of service. This will translate into the programmatic maintenance budget and also maintenance crew’s allocation of time to different BMPs.

8. The Maintenance Paper Trail:

The actual maintenance plan is only one document in the maintenance paper trail that serves to communicate schedules, expectations, and reporting from property owners to property managers and crews. Other components of the paper trail can include:

a. A memorandum of understanding (e.g., as part of a grant project) between, say, grant recipient organizations and responsible maintenance entities outlining expectations, general approach (e.g., using sustainable practices), and funding for maintenance.

b. Some organizations use RFPs or other procurement tools to obtain maintenance services. These documents can be accompanied by a statement of intent noting maintenance expectations, signed prior to construction by the property owner or manager. This statement can in fact be page 1 of the written maintenance plan and specifications. See the end of this article for sample language (provided by Jason Swope, CBLP Coordinator for MD, DC, and WV).

c. The maintenance plan should also include inspection and completed work task forms as part of the communication chain between maintenance contractors (or in-house staff) and property managers. This helps ensure that maintenance is taking place in response to inspection findings and the plan’s specifications. Sample instructions for these forms are also provided below.

Well, that is not too much to ask, is it?

I offer these insights largely because my own efforts to come up with an O&M plan that meets all these criteria have been inadequate. Meeting all of the recommendations above in a way that doesn’t result in the great American multi-volume opus on BMP maintenance (that, surely, few would read) is perhaps a blue sky aspiration for many designers, site owners, and maintenance crews. However, biting off some of it and continuing to improve is the main point.

Anyone out there ready and willing to develop or perhaps modify an existing app?

David J. Hirschman, [email protected]

Thanks to Jason Swope and all of my CBLP colleagues for constructive input on this article.

Selected Resources & References on Stormwater BMP Maintenance

The Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay (ACB), with assistance from CBLP, has assembled the Stormwater Maintenance Resource Center. The website has links to multiple guidance documents on stormwater O&M.

ACB’s Resource Center has links to many resources. Below, are links to selected ones that exemplify certain features of O&M guidance. Note that there are many great resources at the ACB site, so the list below simply represents a few that have caught our eye, but there are other excellent ones in the Resource Center.

The Chesapeake Stormwater Network’s Bioretention Illustrated is a good example of visual triggers to prompt specific maintenance responses.

Philadelphia Water’s Green Stormwater Infrastructure Maintenance Manual is very graphical with helpful (but not excessive) text and also tables and checklists. The manual also addressed routine versus non-routine maintenance (termed reactive maintenance in the manual).

Seattle Public Utility’s Green Stormwater Operation & Maintenance Manual articulates the important level of service construct tied to visual indicators of needed maintenance.

The New York Department of Environmental Conservation Maintenance Guidance provides checklists for BMP owners and municipal staff with triggers to follow-up maintenance actions.

As mentioned above, CBLP’s Sustainable Landscape Maintenance Manual for the Chesapeake Bay Watershed provides guidance and maintenance planning templates, including BMP-specific templates. The manual can be downloaded or hard copies can be purchased.

Sample Language for RFPs and Inspection and Work Completed Forms (thanks to Jason Swope)

Sample Statement of Intent for use in RFPs and/or as Page 1 of the Maintenance Plan:

“It is the desire of the owners to manage the stormwater BMP’s in an environmentally conscious and sustainable manner The specifications outlined below reflect our intent to maintain the BMP’s so that they provide the maximum stormwater treatment and ecosystem services while minimizing air, water, and soil pollution. Please read all specifications carefully and prepare your bid to accurately reflect the scope of services listed.”

Sample Language/Instructions about ongoing documentation of inspections and completed work:

“The contractor shall email documentation of work performed within 7 days of completion. This notification shall include the date and scope of work performed, before and after photos, and a completed inspection report.”

Weed whackers beware. We got this!