We donned our navy-blue coveralls, helmets, headlamps, and gloves and headed up Cave Hill on the trail. After short steep hike, the cave gaped open behind a locked gate to the right. We descended some stairs hued into the limestone rock by long-ago adventurers, and soon were in a giant room filled with various formations. Our party consisted of David, Ellen, myself, and our guides Austin and Daniel. David was there to scope out the setting for promotional videos featuring the “wild caves” of Grand Caverns in Grottoes, Virginia.

Many people are familiar with the many “show caves” in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley (Luray Caverns, Shenandoah Caverns, Endless Caverns, and Natural Bridge Caverns, to name a few). These show caverns feature tours led by guides along well-worn pathways with various features illuminated by internal lighting. It’s a wonderful outing for families, some venues even hosting special events and weddings. It’s also a good thing that these caves represent a small percentage of the total, since the lights, foot traffic, and fingering of cave features exacts a toll on the sensitive cave ecology.

Grand Caverns also offers an alternative for the more adventurous visitors, with tours through “wild caves,” such as Fountain Cave, the cave our party was visiting. While still completely safe, these tours allow for scrambling, climbing, descending, and even rolling through cave features, with the only light provided by the participants’ headlamps. You need good, grippy footwear, and the tour will provide the coveralls, helmets, headlamps, and even some grippy gloves. The guides provide full navigational proficiency and even instruct you on which formations you can use for handholds and footholds, and which you should avoid because they are still forming and vulnerable to damage.

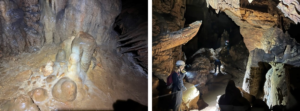

Left: Grottoes Parks Director Austin Shank illuminates some of Fountain Cave’s remarkable formations in one of the larger rooms. Right: David Verde from DV Entertainment descends a steep section of “The Gauntlet,” spotted by caving guide, Daniel (Photos: D. Hirschman)

Grand Caverns happens to be the oldest continuously-operated show cave in the U.S., dating back to 1806. The caverns themselves were stumbled upon in 1804 by Bernard Weyer while searching for one of his hunting traps. The cave and surrounding property have changed ownership over the years, but is now owned and operated by the Town of Grottoes as part of the Grand Caverns Park, a beautiful park along the banks of the South River.

Why does the Shenandoah Valley have so many caves? The answer is “karst.”

Karst is a landscape where soluble rocks, such as limestone and dolomite, dissolve over time to form sinkholes, caves, sinking streams, and other formations. Many of these formations are the remnants of ancient, vast shallow seas where the shells and secretions of a multitude of sea creatures accumulated in layers. Much of the world’s population (over 25 percent) lives on or depends on karst for water supply, and 25% of the U.S. is comprised of karst. It’s a big deal in the world of water (think Florida’s collapsing sinkholes, famous tourist caves in Kentucky and New Mexico, and sinkhole-pocked landscapes in our own Shenandoah Valley and Ridge & Valley provinces).

Left: Don’t touch! This stalagmite is still in the process of forming on the cave floor, while others are many thousands of years old. Right: David Verde and crew set up a cable cam to get a “fly over” of cave formations (Photos: D. Hirschman).

Caves are also known for harboring many species, some very rare, of salamander, spiders, millipedes, beetles, isopods, amphipods, crustaceans, and even blind cave fish (found in Tennessee and Kentucky) that have evolved in and adapted to the dark recesses of the cave environment, not to mention a tragically-declining bat population due to White Nose Syndrome. You may even encounter an Eastern phoebe nesting in a rock nook near the cave entrance.

Worldwide, there is a lot of karst in many diverse places: Madagascar, China, Israel and Palestine, Japan, Philippines, France, Slovenia, Spain, and the United Kingdom, to name just a few. There is even a category of “salt karst” where caverns have formed in marls and sands, such as in Chile’s Cordillera de la Sal.

I first got involved in karst during my graduate school days at Virginia Tech. I was doing a project on the relationship between karst and land use planning. As many know, karst landscapes have a particular vulnerability to water pollution because contaminants can easily find their way into the ground through sinkholes, sinking streams, fissures, and other karst features. Thus, construction of roads, septic systems, detention ponds, industries, and other land uses must take certain precautions, including management of stormwater.

In addition, adding runoff to karst features, pumping groundwater, and weather events such as hurricanes and droughts can cause sinkholes to form, expand, and even collapse in dramatic fashion (at times, this has included sections of I-81, which cuts right up along the Shenandoah Valley’s karst region; Florida has seen the most notorious and catastrophic sinkhole collapses). Thus, karst areas are both vulnerable to pollution and represent a natural hazard.

During my aforementioned graduate school days, I had just finished giving a presentation about karst and land use at a professional conference.

If you say “karst areas” ten time fast, you will understand the next part of this story.

A young man from the audience approached me after the presentation. He expressed appreciation for my talk, but also had a confused expression on his face. Finally, he asked, “what does water pollution have to do with car stereos?”

Over thirty years later, I am still searching for the answer to that question.

David J. Hirschman, dave@hirschmanwater.com

My sincere thanks go to David Verde from DV Entertainment, Ellen Kanzinger, Grottoes Parks & Tourism Director Austin Shank, and caving guide Daniel for arranging and leading the Fountain Cave exploration.

A Few References & Resources (there are many, many more out there!)

What’s Living in Your Cave? By Will Orndorff, Virginia DCE

The Classification and Mapping of Cave and Karst Resources, The Landscape Partnership

The Science Behind Florida’s Sinkhole Epidemic, Smithsonian Magazine, May 24, 2018 (Chris Bodenner)