Canal Boats, Locomotives, Interstate Highways. . .A River Runs Along It

Last fall, I rode my bike along the C&O towpath and the Great Alleghany Passage, following rivers for most of the journey. The C&O traces the banks of the Potomac River from Georgetown in Washington D.C. to Cumberland, MD. Travelling at the “speed of bike” is suitably slow to allow one to ponder the landscape, how it got to be the way it is today, and how transportation infrastructure has intersected with the river corridor over the years.

I stopped at various exhibits to learn about the history of the canal system. At the visitor center in Cumberland, MD, one can walk into a scale replica of a canal boat and learn about the boats, the engineering of the canal system, and the everyday life of those who lived and worked along the canal. Most exhibits along the way included archival photos. After viewing many of these exhibits, it became clear that the river of those days was something completely different than the bucolic, forest-lined river corridor I was experiencing from my bike seat.

Some of the old photos showed nary of tree or shrub in what was clearly an industrialized landscape. It was hard to tell from the black and white archival photos, but the river looked like it had taken quite a beating from the assembled boats, mules, wagons, roads, towns, storage yards, construction zones, and worksites.

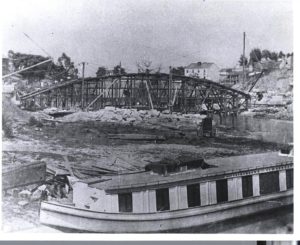

The river corridor and canal were bustling construction zones from 1828 through 1850. The first spadeful of dirt was turned by President John Quincy Adams in 1828, on July 4 no less. https://www.nps.gov/choh/learn/historyculture/canalconstruction.htm Courtesy: National Park Service, Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park, construction along the canal, www.nps.gov/choh/

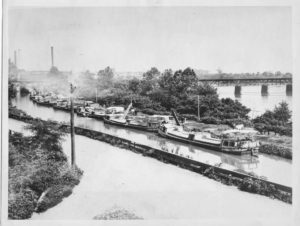

This photo is from Cushwa Basin in Williamsport, MD. For these folks, the river was an intimate companion as they lived and worked along its banks. Courtesy: National Park Service, Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park, canal boats at Cushwa Basin, www.nps.gov/choh/

Here the canal boat are lined up at Georgetown. Courtesy: National Park Service, Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park, boats in the canal at Georgetown, www.nps.gov/choh/

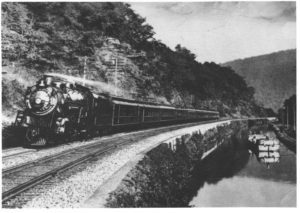

And then came the railroads that carved out tracks along the riverbanks and built numerous bridges and tunnels. Our rivers were indeed bustling linear commercial corridors.

This archival photo shows a canal boat alongside a locomotive, demonstrating the evolution of transportation systems that both relied on the river corridors. Courtesy: National Park Service, Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park, locomotive alongside canal boat, www.nps.gov/choh/

Today’s planners bemoan that our recent automobile-oriented developments have turned their backs to the local waterways. Indeed, many urban river corridors today offer views of the backsides of shopping centers and factories, along with infrastructure both old and new.

However, it is also clear that when we DID face the river, it was because it was necessary and expedient for the commercial enterprises of the day. Certainly, the people and towns along the river had intimate knowledge of its water, but were also in a position to use those waters roughly in pursuit of various commercial ventures and as a repository for waste products. Periodic floods and droughts set up an adversarial relationship whereby more engineering was needed to try to control the system that had its wild, unpredictable (and economically-destructive) side. This was far from a landscape of recreational trails, canoe liveries, cafes, and the vision of river-oriented development we aspire to today.

When commerce moved from the rivers to the interstate highways, the river corridors in many ways became forgotten landscapes. Eventually, the rail trails and urban trail systems replaced the industrialized landscape, the forest grew, and the stewards of these systems (e.g., National Park Service, park and trail advocacy groups, such as the C&O Canal Trust) rehabilitated the locks, toll houses, and other structures so that we could learn about the engineering feats of our forebears, which were indeed impressive. Notably, water quality improvements driven by the Clean Water Act allowed river corridors to become more inviting for recreation and interpretation.

As for interstate highways, they certainly were no godsend for the rivers. Their impacts tend to extend many miles downstream with stunning volumes of uncontrolled stormwater and associated pollutants. This is our modern legacy of transportation infrastructure and rivers.

The evoluation of transportation infrastructure continues. Here is a photo from my local river, the Rivanna River, showing both the railroad and Interstate 64 crossings, both currently in use. Photo: David J. Hirschman

The C&O canal began construction nearly 200 years ago. What do you think our interstate corridors will look like in another 200 years? Maybe they will be the long-distance trails systems of the future, complete with historical exhibits showing 18-wheelers and traffic jams to educate future populations on the quaint transportation systems of the past? It is my sincere hope that bicycles will still be around, and that may be a great way to explore these future interstate linear recreation parks.

The interstates shifted the hubs of commerce and transportation away from the river corridors (except for railroads, that still use these corridors – day and night – as you will learn if you camp along the C&O), and brought problems of their own for waterways. Transportation systems, while exhibiting incredible feats of engineering and ingenuity, have been tough on our rivers from era to era. Given that we are inclined as a species to get from one place to another, we will have to exercise our collective creative forces to bring more harmony between transportation infrastructure and rivers.

I would like to conclude with a pitch for the C&O Canal Trust, the official non-profit partner of the Chesapeake & Ohio National Historic Park. In partnership, these organizations raise funds to preserve, restore, interpret, and educate communities about the canal system. The Trust will be happy to accept your donations.

https://www.nps.gov/choh/index.htm

Let me know your thoughts on transportation infrastructure and rivers: dave@hirschmanwater.com

A more intimate photo of life along the C&O canal. Courtesy: National Park Service, Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park, above the aqueduct bridge, www.nps.gov/choh/

The C&O towpath, pictured here in October 2019, is a wonderful place to explore the Potomac River and history of transportation in this part of the country. Photo: David J. Hirschman